Two weeks ago, we visited a hospital far in the mountains where they took care of children who were mentally and physically handicapped severely. It was sad to read their charts, how some of them ended up there -- some parents didn't want to take care of them anymore because their handicap was too much to handle, while others hadn't wanted them in the first place, abusing them until they had to be hospitalized.

But what also shocked me was when I saw full grown adults who weren't all that different from the children -- just a bit larger in size. With medicine's advancement, the severely handicapped children can now grow up and live on to become adults. It must be something to be celebrated. But to be totally honest, I felt this unfathomable sadness when I saw the adults lying side by side on the futons, hardly able to move, not being able to say one word. I was embarrassed to feel that way, because who was I to decide that they were unhappy or that they couldn't even tell if they were happy or not?

Back in the university hospital, the doctors were discussing what they should do about a two year old boy with cerebral palsy whose mother had left the hospital without notice. The boy was so small, soundly asleep in the hospital's large bed, and I thought about the adults I saw in the hospital in the mountains, the future versions of the little boy. Of course, the doctors had done their best to save him, and were still trying to find the best place for him to live.

Because every life is worth living. Every life.

2015年9月12日土曜日

2015年6月25日木曜日

singing in the rain

It's been raining almost every single day where I live, I haven't been able to sleep well for whatever reason, but the training goes on, and I've been training at the neurology department this week. Today, we visited a hospital where they take care of patients with intractable diseases such as muscular dystrophy and ALS.

One of the first patients we met was a man in is early sixties with ALS who could no longer move his body (including his respiratory muscles -- he was connected to a ventilator) but was still able to move his facial muscles. I knew they used alphabet boards to communicate at that stage, but it was my first time to actually watch a patient do it. The person talking to him would read out the alphabets on the board, and he would blink every time the reader came to the right alphabet. There's an easier way using a computer, but when I watched the man blink with all his strength just to choose a single alphabet in a single word in a single sentence, it felt a bit like having a small carrier pigeon fly back and forth in a small room with one letter at a time, and I couldn't help but realize how lucky we were to be able to communicate so easily. When we left the room, the patient moved his mouth to wish us good luck, and I think it made us all feel relieved that he looked rather cheerful.

But the next patient we saw was a woman in her forties who had been diagnose in her twenties, and was now unable to move even her facial muscles. The doctor explained that it was a case of locked-in syndrome, which I think actually leaves the patient with control over her eyeballs and eyelids, but apparently, she couldn't even move her eyes, so there was no way to communicate her feelings. Her sensory nerves were intact, and she was totally conscious, so she could still hear what others were saying and see what was right in front of her, but no one could tell what she wanted, and she had been that way for the past decade or so. After training as a student doctor for three months at seven departments, this illness is the one I fear most.

Having said that, I don't mean to say that she must have been unhappy. Before we left the hospital, the doctor told us a story about a couple with a son who was born with muscular dystrophy (which is a X-linked recessive disease): when the wife conceived their second child, there was a new option they hadn't had with their first child -- prenatal diagnosis. The wife didn't want to take the test, and was determined to give birth to the baby regardless of his genetic status. However, her husband's parents insisted they get tested, and as a result, they discovered that their second child also had MD. The mother ended up having an abortion, but strongly regretted her decision, especially because she thought it meant that she was unconsciously hoping to let go of her first son as well. She also remembered that many people had told them when he was born that certain babies were born only to parents who could take care of them, and she felt guilty that she had let go of a baby who had "chosen" her.

The patients we met today didn't necessarily look depressed. We didn't get the chance to actually ask about what they thought about their life, but I personally want to believe that all humans have the power to find happiness under any given circumstances. I definitely didn't think it was a bluff when the doctor told us what one patient had said to him: that he was unlucky, but not unhappy. I've thought about the option of prenatal diagnosis a couple of times, but what I thought today was that it was a very arrogant option in a way. Who was I to decide my child was going to become unhappy just because he had a certain gene (or a set of them)? Of course there would be hardships, but any kind of life has hardships. There may be more for him, but he would also have the chance to enjoy happy moments. Even if it was just once, a brief moment, I think it can still be a moment worth living his whole life for. But what I think may not even matter -- the point is that the child will have his own thoughts, his own world, and I can't evaluate it with my sense of value. And at the end of the day, I believe no happiness lasts forever, and when we're feeling happy, it doesn't matter if there are a thousand more moments like that, because right then, we have that, and that's all that matters.

One of the first patients we met was a man in is early sixties with ALS who could no longer move his body (including his respiratory muscles -- he was connected to a ventilator) but was still able to move his facial muscles. I knew they used alphabet boards to communicate at that stage, but it was my first time to actually watch a patient do it. The person talking to him would read out the alphabets on the board, and he would blink every time the reader came to the right alphabet. There's an easier way using a computer, but when I watched the man blink with all his strength just to choose a single alphabet in a single word in a single sentence, it felt a bit like having a small carrier pigeon fly back and forth in a small room with one letter at a time, and I couldn't help but realize how lucky we were to be able to communicate so easily. When we left the room, the patient moved his mouth to wish us good luck, and I think it made us all feel relieved that he looked rather cheerful.

But the next patient we saw was a woman in her forties who had been diagnose in her twenties, and was now unable to move even her facial muscles. The doctor explained that it was a case of locked-in syndrome, which I think actually leaves the patient with control over her eyeballs and eyelids, but apparently, she couldn't even move her eyes, so there was no way to communicate her feelings. Her sensory nerves were intact, and she was totally conscious, so she could still hear what others were saying and see what was right in front of her, but no one could tell what she wanted, and she had been that way for the past decade or so. After training as a student doctor for three months at seven departments, this illness is the one I fear most.

Having said that, I don't mean to say that she must have been unhappy. Before we left the hospital, the doctor told us a story about a couple with a son who was born with muscular dystrophy (which is a X-linked recessive disease): when the wife conceived their second child, there was a new option they hadn't had with their first child -- prenatal diagnosis. The wife didn't want to take the test, and was determined to give birth to the baby regardless of his genetic status. However, her husband's parents insisted they get tested, and as a result, they discovered that their second child also had MD. The mother ended up having an abortion, but strongly regretted her decision, especially because she thought it meant that she was unconsciously hoping to let go of her first son as well. She also remembered that many people had told them when he was born that certain babies were born only to parents who could take care of them, and she felt guilty that she had let go of a baby who had "chosen" her.

The patients we met today didn't necessarily look depressed. We didn't get the chance to actually ask about what they thought about their life, but I personally want to believe that all humans have the power to find happiness under any given circumstances. I definitely didn't think it was a bluff when the doctor told us what one patient had said to him: that he was unlucky, but not unhappy. I've thought about the option of prenatal diagnosis a couple of times, but what I thought today was that it was a very arrogant option in a way. Who was I to decide my child was going to become unhappy just because he had a certain gene (or a set of them)? Of course there would be hardships, but any kind of life has hardships. There may be more for him, but he would also have the chance to enjoy happy moments. Even if it was just once, a brief moment, I think it can still be a moment worth living his whole life for. But what I think may not even matter -- the point is that the child will have his own thoughts, his own world, and I can't evaluate it with my sense of value. And at the end of the day, I believe no happiness lasts forever, and when we're feeling happy, it doesn't matter if there are a thousand more moments like that, because right then, we have that, and that's all that matters.

2014年10月2日木曜日

big dreams

Last night, we had a welcome party for new students, and their big dreams reminded me of my own dream I'd had when I entered med school.

He said his dream was to work as a member of Doctors without Borders and eventually get a job in the WHO. I think it's a great dream, and regarding the fact that he has already worked in Uganda, I'm pretty sure he has the guts to make his dreams come true. The only problem I had with him (apart from the fact that he kept spitting at me and into my plate with every other word he spoke) was that he didn't seem to see what was right in front of him because he was too busy looking at Africa. He wasn't a bad person at all; I actually even liked him a bit, but I thought I didn't want to be like him. I don't want to forget the things lying in front of me. I guess I've realized lately that it's really the small things that matter to me.

A couple of weeks ago, our emergency medicine professor told us about how he had saved a three month year old baby and he was outraged that some stupid doctor had criticized him for saving such a child -- hardly a human being -- who would have to live the rest of his life with serious disabilities. I was amazed that the professor seemed to have no doubt whatsoever that what he had done was perfectly "right". I realize that when you practice medicine, you sometimes end up forcing upon patients (and their families) the sense of value that being alive means everything. Even if you can't walk or talk or go to the toilet on your own, it's great just being alive. I want to believe it's true. We need to make a society that makes this true. But in reality, I'm not quite sure. Doctors save lives and feel happy. But what do they know about what happens to those lives they save? After all, who feeds the kid for the rest of his life? Who can guarantee that those lives in developing countries saved by foreign doctors who return home to their warm beds and meals, find the same warm shelter and enough food? What if the country can't support that many people?

I don't want to forget that it's harder to save lives than we usually think it is. I want to remember that we can be wrong. I don't know if I still want to work abroad, but regardless of where I work, I want to live with humility.

2014年7月15日火曜日

three minutes

All I've been writing about lately has been my shadowing experiences but here's another one. If anyone has felt angry or even hurt by a doctor's insensitive attitude, I want to apologize on behalf and promise I will try my best not to be the same (when I finally become a doctor).

The other day, I shadowed a physician specializing in liver (and the surrounding organs). One of the outpatients came to get the results of her test and it turned out she had some hepatitic virus in her blood and that her liver had some kind of inflamation. The doctor wanted to do a biopsy and he needed the patient's consent. But the patient's daughter asked most of the questions and the doctor's answers were blunt. The patient just sat there with a worried face, not knowing what to do. Amidst an awkward silence, the doctor started glancing through a chart of another patient while the patient in front of him thought about the options provided. I totally understood how busy the doctor was -- he had so many patients waiting; the list went on forever. His behavior may have been unavoidable for the greatest happiness of the greatest number. But I could tell he was also in a bad mood (partly because his computer kept bringing up the wrong kanji). And this is where things started going worse.

He leaned back in his chair, glanced at the patient, and told her that he himself had never caused hemorrhage that required transfusion but that he had seen a horrible case in the past when he had been a resident. He laughed a bit, and the patient just nodded. It's of course important to inform the patient of the risks but it's useless to stir up her anxiety with an accident that occurred thirty years ago. Some doctors bring up so much statistics and even talk about cases of other patients under different conditions. If the patient wants all that information, she will ask for it, or she could even look it up herself. What's good about getting informed by a doctor, in my opinion, is that the doctor is not a computer; he becomes a human filter that picks up necessary information for the patient and provides it with consideration towards her feelings. All she needs is a clear explanation of what the biopsy is for and how it will be done, and what the risks are in her case. Not the next patient. When I become a doctor, my duty will be to treat as many patients, but I still don't want to forget to focus on the patient I am seeing at that moment.

The same day, I happened to listen to an interview with Ed Sheeran, and he described how a brief exchange with another singer had changed his life. It had only been three minutes for that other singer and it might've meant nothing, but it meant his life to Ed Sheeran. That's why he thinks it's important that he always leaves his personal emotions backstage or in the car. His fans are going to meet him only once for less than three minutes, and if he acts like a jerk, he might pluck a bud that otherwise would've bloomed as a great musician like himself. Doctors don't change lives like that. A liver biopsy being postponed for a week may not change a patient's prognosis. But I think it's the same three minutes. "Another three minutes" for a doctor means more than that to a patient.

The other day, I shadowed a physician specializing in liver (and the surrounding organs). One of the outpatients came to get the results of her test and it turned out she had some hepatitic virus in her blood and that her liver had some kind of inflamation. The doctor wanted to do a biopsy and he needed the patient's consent. But the patient's daughter asked most of the questions and the doctor's answers were blunt. The patient just sat there with a worried face, not knowing what to do. Amidst an awkward silence, the doctor started glancing through a chart of another patient while the patient in front of him thought about the options provided. I totally understood how busy the doctor was -- he had so many patients waiting; the list went on forever. His behavior may have been unavoidable for the greatest happiness of the greatest number. But I could tell he was also in a bad mood (partly because his computer kept bringing up the wrong kanji). And this is where things started going worse.

He leaned back in his chair, glanced at the patient, and told her that he himself had never caused hemorrhage that required transfusion but that he had seen a horrible case in the past when he had been a resident. He laughed a bit, and the patient just nodded. It's of course important to inform the patient of the risks but it's useless to stir up her anxiety with an accident that occurred thirty years ago. Some doctors bring up so much statistics and even talk about cases of other patients under different conditions. If the patient wants all that information, she will ask for it, or she could even look it up herself. What's good about getting informed by a doctor, in my opinion, is that the doctor is not a computer; he becomes a human filter that picks up necessary information for the patient and provides it with consideration towards her feelings. All she needs is a clear explanation of what the biopsy is for and how it will be done, and what the risks are in her case. Not the next patient. When I become a doctor, my duty will be to treat as many patients, but I still don't want to forget to focus on the patient I am seeing at that moment.

The same day, I happened to listen to an interview with Ed Sheeran, and he described how a brief exchange with another singer had changed his life. It had only been three minutes for that other singer and it might've meant nothing, but it meant his life to Ed Sheeran. That's why he thinks it's important that he always leaves his personal emotions backstage or in the car. His fans are going to meet him only once for less than three minutes, and if he acts like a jerk, he might pluck a bud that otherwise would've bloomed as a great musician like himself. Doctors don't change lives like that. A liver biopsy being postponed for a week may not change a patient's prognosis. But I think it's the same three minutes. "Another three minutes" for a doctor means more than that to a patient.

2014年7月4日金曜日

0~1 year olds

A quick note of nursery shadowing round 2:

1. Kids can tell if you're a stranger from when they're around a couple months old.

2. Kids aren't interested in one another until they're around two years old.

3. They're fine with tasteless foods until they taste all the yummy stuff out in the world.

4. They're more interested in picking at pieces of Velcros on toys rather than toys themselves.

5. Some kids bite their peers when they fight for toys. (Reminded me of a certain soccer player.)

6. The yellow lines on their diapers change blue when they've peed.

7. You can feel the gelatin in their diapers when they've peed.

8. When they're crying, it's because they need a warm hug or a bottle of milk or they've peed.

9. The reason the nursery staffs don't throw away used diapers and give them back to parents is NOT because the parents check the contents when they get home. They have to take the diaper to the doctor when the kid is sick but usually, no one checks. They just stink. So the nursery has decided to stop giving back wet diapers from next month.

10. Some parents prefer cloth diapers because kids can feel the uncomfortable wetness when they've peed and they learn to use the bathroom earlier than kids with expensive paper diapers.

11. Most kids are messy and have runny nose. They drool over your shirt and then look back at you with innocent eyes.

12. And they're so adorable it's heartbreaking when you leave them and they start crying.

1. Kids can tell if you're a stranger from when they're around a couple months old.

2. Kids aren't interested in one another until they're around two years old.

3. They're fine with tasteless foods until they taste all the yummy stuff out in the world.

4. They're more interested in picking at pieces of Velcros on toys rather than toys themselves.

5. Some kids bite their peers when they fight for toys. (Reminded me of a certain soccer player.)

6. The yellow lines on their diapers change blue when they've peed.

7. You can feel the gelatin in their diapers when they've peed.

8. When they're crying, it's because they need a warm hug or a bottle of milk or they've peed.

9. The reason the nursery staffs don't throw away used diapers and give them back to parents is NOT because the parents check the contents when they get home. They have to take the diaper to the doctor when the kid is sick but usually, no one checks. They just stink. So the nursery has decided to stop giving back wet diapers from next month.

10. Some parents prefer cloth diapers because kids can feel the uncomfortable wetness when they've peed and they learn to use the bathroom earlier than kids with expensive paper diapers.

11. Most kids are messy and have runny nose. They drool over your shirt and then look back at you with innocent eyes.

12. And they're so adorable it's heartbreaking when you leave them and they start crying.

2014年6月28日土曜日

two year olds

I still remember about the day I stopped crying at nursery school. Until then, I think I stayed by the glass door and cried as I watched my mother disappear into the distance, but that morning, I went into the playroom and decided that I wasn't going to cry. The sliding door closed, and I held back my tears as I picked up a wooden block to force myself to focus on playing with it. I was three years old.

When we moved to New Zealand and I started going to kindergarten, the whole process started all over again. I cried like mad every time my mother tried to leave me. I don't really remember when it was that I finally stopped crying. Maybe it was when Kate came up to play with me.

Today, I went to visit a nursery school as it was part of our shadowing program. I was put into the rabbit class with 17 cute two year olds. The hardest part was making them finish their lunch. They do all kinds of stuff to avoid eating what they don't like: they drop spoons on purpose, drop the food on purpose, walk around the room, stick their hands under your apron to touch your breasts, make faces, and cry. It's amazing how they change their attitude according to who's helping them eat. A girl who would keep shaking her head to me would open her mouth when a strict teacher comes to force the food into her mouth. They can't control their pee, and yet they know how to manipulate college students with huge drops of tears and vague complaints.

One episode that might be worth noting -- a girl I was feeding (Erika) said she was finished and left her seat to pick up her toothbrush, and then the girl sitting next to her started crying, apparently because she thought it was unfair that Erika got to leave her veggies while she still had to eat hers. It reminded me of a monkey experiment that proved that even monkeys didn't accept unfairness (you can watch it here).

Later when Erika had to get changed for her nap, she came up to me with her bag packed with diapers but instead of giving me a diaper, she handed me a pair of pink undies and insisted she was going to be totally fine with that while she made me take off her wet diaper. Well, at least she didn't spit lettuce on me!

On a side note, after nap time was over, they were served a cup of milk with their snacks, and I winced as the teacher gave me my cup. I don't like milk (my mom could hardly breast-feed me). When I took a sip, it was tepid and it just tasted really bad. Having to drink it with messy kids made it harder, but what could I say after telling them they shouldn't be so picky? In New Zealand, I didn't have school lunch, so when I came back to Japan, I told the teacher I couldn't drink milk because I didn't like it. She told me I couldn't say that. I didn't quite understand her, but eventually, I learned to accept the only choice. School lunch does make kids grow up -- physically and mentally.

When we moved to New Zealand and I started going to kindergarten, the whole process started all over again. I cried like mad every time my mother tried to leave me. I don't really remember when it was that I finally stopped crying. Maybe it was when Kate came up to play with me.

Today, I went to visit a nursery school as it was part of our shadowing program. I was put into the rabbit class with 17 cute two year olds. The hardest part was making them finish their lunch. They do all kinds of stuff to avoid eating what they don't like: they drop spoons on purpose, drop the food on purpose, walk around the room, stick their hands under your apron to touch your breasts, make faces, and cry. It's amazing how they change their attitude according to who's helping them eat. A girl who would keep shaking her head to me would open her mouth when a strict teacher comes to force the food into her mouth. They can't control their pee, and yet they know how to manipulate college students with huge drops of tears and vague complaints.

One episode that might be worth noting -- a girl I was feeding (Erika) said she was finished and left her seat to pick up her toothbrush, and then the girl sitting next to her started crying, apparently because she thought it was unfair that Erika got to leave her veggies while she still had to eat hers. It reminded me of a monkey experiment that proved that even monkeys didn't accept unfairness (you can watch it here).

Later when Erika had to get changed for her nap, she came up to me with her bag packed with diapers but instead of giving me a diaper, she handed me a pair of pink undies and insisted she was going to be totally fine with that while she made me take off her wet diaper. Well, at least she didn't spit lettuce on me!

On a side note, after nap time was over, they were served a cup of milk with their snacks, and I winced as the teacher gave me my cup. I don't like milk (my mom could hardly breast-feed me). When I took a sip, it was tepid and it just tasted really bad. Having to drink it with messy kids made it harder, but what could I say after telling them they shouldn't be so picky? In New Zealand, I didn't have school lunch, so when I came back to Japan, I told the teacher I couldn't drink milk because I didn't like it. She told me I couldn't say that. I didn't quite understand her, but eventually, I learned to accept the only choice. School lunch does make kids grow up -- physically and mentally.

2014年3月8日土曜日

on death and dying

Death is just a moment when dying ends

-Montaigne

Finished reading On Death and Dying by Dr. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross. It's a study on death and dying -- how each individual patient copes with his last yet greatest ordeal in life. It contains many dialogues between the interviewers (the author with the hospital chaplain) and the patient who found the interviews as a chance to let out their suppressed concerns and emotions as well as to teach the medical professionals and pass something on.

Several things I want to remember (mostly from the last two chapters):

1. Terminally ill patients are aware of the seriousness of their illness whether they are told or not. Those who are not told explicitly know it anyway from the implicit messages or altered behavior of relatives and staff. Those who are told explicitly appreciate it unless they are told coldly and without preparation or follow-up, or in a manner that leaves no hope.

2. Leave hope when telling the truth. No matter the stage of illness or coping mechanisms used, all patients maintain some form of hope until the last moment.

3. We have to take a good hard look at our own attitude towards death and dying before we can sit quietly and without anxiety next to a terminally ill patient. The most important thing is to let him know that we are ready and willing to share some of his concerns.

4. For the patient death itself is not the problem, but dying is feared because of the accompanying sense of hopelessness, helplessness, and isolation.

5. Dying patients has the need ro leave something behind. They want something that will continue to live perhaps after their death and become immortal in a little way.

On a side note, the Japanese translation of the title is 死ぬ瞬間 which literally means "the moment of death". I haven't read the translation so I'm not sure what the translator meant but this book is not about the moment of death; it's about the suffering and eventual acceptance that comes before that moment in life; it's more about dying - the last process of living - than about death itself. But then again, I think there's no such word as "dying" in Japanese. Interesting.

-Montaigne

Finished reading On Death and Dying by Dr. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross. It's a study on death and dying -- how each individual patient copes with his last yet greatest ordeal in life. It contains many dialogues between the interviewers (the author with the hospital chaplain) and the patient who found the interviews as a chance to let out their suppressed concerns and emotions as well as to teach the medical professionals and pass something on.

Several things I want to remember (mostly from the last two chapters):

1. Terminally ill patients are aware of the seriousness of their illness whether they are told or not. Those who are not told explicitly know it anyway from the implicit messages or altered behavior of relatives and staff. Those who are told explicitly appreciate it unless they are told coldly and without preparation or follow-up, or in a manner that leaves no hope.

2. Leave hope when telling the truth. No matter the stage of illness or coping mechanisms used, all patients maintain some form of hope until the last moment.

3. We have to take a good hard look at our own attitude towards death and dying before we can sit quietly and without anxiety next to a terminally ill patient. The most important thing is to let him know that we are ready and willing to share some of his concerns.

4. For the patient death itself is not the problem, but dying is feared because of the accompanying sense of hopelessness, helplessness, and isolation.

5. Dying patients has the need ro leave something behind. They want something that will continue to live perhaps after their death and become immortal in a little way.

On a side note, the Japanese translation of the title is 死ぬ瞬間 which literally means "the moment of death". I haven't read the translation so I'm not sure what the translator meant but this book is not about the moment of death; it's about the suffering and eventual acceptance that comes before that moment in life; it's more about dying - the last process of living - than about death itself. But then again, I think there's no such word as "dying" in Japanese. Interesting.

2014年3月1日土曜日

understanding pain

Today I went to a mental hospital to listen to a public lecture on dementia only to doze off until the lecture was over and people started asking questions. My mother had come too, and curiously, we ended up having very different impressions on the director who gave the lecture -- she thought he was overbearing and that he looked down on patients' families; I thought he was humorous and had a deep understanding towards patients (or maybe accepted the fact that he did not understand them fully).

An old man (probably around 80) asked a question about his wife who was taken care of at the hospital but was about to be discharged. He was concerned about her roaming habits and asked if it was a good idea to hang a cell phone around her neck and put a name tag on her shirt, to which the director answered that in the first place, we all had to remember that no one roamed because they liked it. Patients roam around because they are anxious; they don't know where they are, they don't know who they are, and so they roam around. He added that maybe the patient didn't want to have a cell phone hanging around her neck; maybe she didn't want to have a name tag on her shirt; and maybe she didn't want to walk around shouting at the whole world that she had Alzheimer's. Maybe she still wants dignity.

My mother pointed out that the director had an overbearing attitude towards the old man who was desperate. He was clearly worried about how to take care of his wife. It wasn't like he didn't think of her as a human being anymore; he was just... worried. He didn't need a lecture on how to let her live with dignity.

A care worker also asked what she should do when patients asked if they could go home. They asked every day, over and over, and she didn't know what to do. The director said that was normal. They were after all "abducted" and thrown into a hospital. We all had to acknowledge that it is practically impossible to convince the patients that they were better off "here" than back at home. We should never pretend "here" was "home". If we let go and just listened to them and accepted their anger and grief, then the patient would eventually find his own way to convince himself about his own situation.

Again, my mother thought the director was looking down on the care worker who probably already knew all that and was still asking the director for his insight. I could see that my mother had felt exactly the same as how I had felt towards the brain surgeon who talked about brain death and organ transplantation last month.

Maybe the director did look down on families. After all, he was a pro at taking care of patients with mental problems while families were always amateurs struggling to accept the unacceptable -- the process of losing someone they love -- and trying to take care of them while dealing with other problems in life; of course they were not going to be perfect, they were going to be inconsiderate towards the patient at times. But as my mother said, that doesn't mean the doctor can just sit back and give them a lecture like he knows everything.

When I said I didn't really think the director was that high-handed and added that it might have been because I was the same kind of human, I didn't really mean it, but my mother said maybe I was right. "You're too good at everything."

I don't know what she really meant, but I hope I can become a doctor who can understand the pain of both the patient and his family.

An old man (probably around 80) asked a question about his wife who was taken care of at the hospital but was about to be discharged. He was concerned about her roaming habits and asked if it was a good idea to hang a cell phone around her neck and put a name tag on her shirt, to which the director answered that in the first place, we all had to remember that no one roamed because they liked it. Patients roam around because they are anxious; they don't know where they are, they don't know who they are, and so they roam around. He added that maybe the patient didn't want to have a cell phone hanging around her neck; maybe she didn't want to have a name tag on her shirt; and maybe she didn't want to walk around shouting at the whole world that she had Alzheimer's. Maybe she still wants dignity.

My mother pointed out that the director had an overbearing attitude towards the old man who was desperate. He was clearly worried about how to take care of his wife. It wasn't like he didn't think of her as a human being anymore; he was just... worried. He didn't need a lecture on how to let her live with dignity.

A care worker also asked what she should do when patients asked if they could go home. They asked every day, over and over, and she didn't know what to do. The director said that was normal. They were after all "abducted" and thrown into a hospital. We all had to acknowledge that it is practically impossible to convince the patients that they were better off "here" than back at home. We should never pretend "here" was "home". If we let go and just listened to them and accepted their anger and grief, then the patient would eventually find his own way to convince himself about his own situation.

Again, my mother thought the director was looking down on the care worker who probably already knew all that and was still asking the director for his insight. I could see that my mother had felt exactly the same as how I had felt towards the brain surgeon who talked about brain death and organ transplantation last month.

Maybe the director did look down on families. After all, he was a pro at taking care of patients with mental problems while families were always amateurs struggling to accept the unacceptable -- the process of losing someone they love -- and trying to take care of them while dealing with other problems in life; of course they were not going to be perfect, they were going to be inconsiderate towards the patient at times. But as my mother said, that doesn't mean the doctor can just sit back and give them a lecture like he knows everything.

When I said I didn't really think the director was that high-handed and added that it might have been because I was the same kind of human, I didn't really mean it, but my mother said maybe I was right. "You're too good at everything."

I don't know what she really meant, but I hope I can become a doctor who can understand the pain of both the patient and his family.

2014年2月8日土曜日

recycling

Human recycling. I think that's what organ transplant is in the end. The concept of brain death only emerged when human recycling started. Before that, no one was dead unless their heart stopped beating. Human recycling is wonderful as it saves many lives, but at the same time, it is not the most natural phenomenon on earth and I totally understand that there are many families who have difficulties accepting the fact that a patient's brain death means their death. And if that is why Japan has such a low transplant rate, I think we just have to accept it. But maybe I'm wrong.

Japan is said to have the best skill when it comes to organ transplant and yet we have the worst transplant rate among developed countries. The US still provides 5% of their transplant organs to foreign patients, and the majority goes to Japanese patients who come with hundreds and millions of dollars.

Today, a brain surgeon came to talk to us about organ transplant. It was his 123rd time to give the talk, and he said he was here to give us some "correct knowledge". He seemed to have some very strong feelings towards doctors who didn't present the option of organ transplant to the patients' families, and towards journalists who critisized that families were often unfairly "urged" to consent under some kind of pressure. These people were being the obstacles in preventing the growth of transplant industry in Japan.

According to him, doctors never "urged" families. A doctor's job is to tell the family that the patient will soon be dead and ask if they would consent to organ donation. I think the point the surgeon wanted to make was that we should all accept that it was natural to be asked about organ donation at times of death -- it is out-of-date to regard this type of "request" as insensitive "exploitation". After all, we're living the age of human recycling.

I do understand at a very logical level, but I was not convinced at all on an emotional level (maybe because he spoke so fast and came on pretty strong). I personally think many families will more or less feel that they are "urged", as some journalists (and lawyers) point out. If you dissent, it's literally the same as being asked if you would save someone's life and saying no. The surgeon said doctors were the same as waiters at Mc Donalds -- they offer cheese burgers and chicken nuggets for customers to choose, while we offer the chance of saving a life or not saving a life, for families to choose. I don't think it's the same at all.

He also said the Japanese were too emotional when it came to the definition of death. Being brain dead means being dead in the context of organ transplant, just like red means stop in the context of traffic lights. I don't think it's the same at all. It's easy to accept the latter; it's much much harder to accept death.

A doctor's job is to save patients -- not only those who are right in front of them, but also those who they haven't met. As the surgeon insisted strongly, Japanese doctors do need to learn to bring this subject up in front of families. However, I think it's also important to realize that some families will, in fact, feel urged or even forced to consent. We have to know that it's not the same as offering burgers and nuggets. And we should acknowledge that we are asking families to think about saving someone they don't even know, when all they can think about is the fact that they are about to lose someone they love. It's obviously important we reassure that families who decide not to consent will not be blamed for "killing" anyone.

Japan is said to have the best skill when it comes to organ transplant and yet we have the worst transplant rate among developed countries. The US still provides 5% of their transplant organs to foreign patients, and the majority goes to Japanese patients who come with hundreds and millions of dollars.

Today, a brain surgeon came to talk to us about organ transplant. It was his 123rd time to give the talk, and he said he was here to give us some "correct knowledge". He seemed to have some very strong feelings towards doctors who didn't present the option of organ transplant to the patients' families, and towards journalists who critisized that families were often unfairly "urged" to consent under some kind of pressure. These people were being the obstacles in preventing the growth of transplant industry in Japan.

According to him, doctors never "urged" families. A doctor's job is to tell the family that the patient will soon be dead and ask if they would consent to organ donation. I think the point the surgeon wanted to make was that we should all accept that it was natural to be asked about organ donation at times of death -- it is out-of-date to regard this type of "request" as insensitive "exploitation". After all, we're living the age of human recycling.

I do understand at a very logical level, but I was not convinced at all on an emotional level (maybe because he spoke so fast and came on pretty strong). I personally think many families will more or less feel that they are "urged", as some journalists (and lawyers) point out. If you dissent, it's literally the same as being asked if you would save someone's life and saying no. The surgeon said doctors were the same as waiters at Mc Donalds -- they offer cheese burgers and chicken nuggets for customers to choose, while we offer the chance of saving a life or not saving a life, for families to choose. I don't think it's the same at all.

He also said the Japanese were too emotional when it came to the definition of death. Being brain dead means being dead in the context of organ transplant, just like red means stop in the context of traffic lights. I don't think it's the same at all. It's easy to accept the latter; it's much much harder to accept death.

A doctor's job is to save patients -- not only those who are right in front of them, but also those who they haven't met. As the surgeon insisted strongly, Japanese doctors do need to learn to bring this subject up in front of families. However, I think it's also important to realize that some families will, in fact, feel urged or even forced to consent. We have to know that it's not the same as offering burgers and nuggets. And we should acknowledge that we are asking families to think about saving someone they don't even know, when all they can think about is the fact that they are about to lose someone they love. It's obviously important we reassure that families who decide not to consent will not be blamed for "killing" anyone.

2014年2月2日日曜日

dream cells

In exchange for making each of us original, genes are unfair. Michael Jackson was born black when he wanted to be white. So technology and plastic surgery helped him get what his genes couldn't. Once when he was still alive, I heard someone joke that he had a set of noses and ears in his closet and would pick one every morning to wear for the day. What if we could do something similar with our organs?

Tissue engineering (or regenerative medicine) seems to be a huge trend these days. In the future, human bodies might be repairable like cars. If your kidney fails, you get a new one made from your own somatic cell. If you need a new liver, you will never have to wait for a doner. If your son is born with a heart disease, you will never have to hope (even for a second) that another child will be brain dead so that he can provide a new heart for your son. One day, you may never have to watch your loved ones die. At least, no nation would have to pay billions of money for dialysis, and therefore, the money can be used to enhance our lives in other ways. It's a technology no one could ever have imagined 100 years ago; it's full of dreams. It's exciting.

And yet, I wonder if we're really heading the right way.

A young Japanese researcher recently published her discovery of a revolutional way of making stems cells from somatic cells by merely exposing them to low-pH (the link is below**). When she first submitted her paper, however, the editor told her that she had mocked the long history of cellular biology. The reason is obvious -- the editor had been soaked in preconception he had formed over many years of editing and researching; he could not believe, or accept that a cell could be reprogrammed with such a simple method.

Steve Jobs said in his famous speech that death was nature's best invention. I agree. Altertion of generations is essential to the progress of human society. The only way the old can give way to the new is to die, or get a new brain with no preconception -- every couple decades, you get a set of new organs along with a new brain for your birthday. Except then, it's not really you. It's just a human with the same set of genes as you. So rather than getting a new brain in a "100 year old" body (with organs of various ages), you might as well be born as a different being with a different set of genes. Then it's called evolution.

Either way, you don't really want a brand new brain. The realistic scenario is probably that you get a set of new neurons that would work along with your old ones so that you can still be you. By the time you reach seventy, you have a brain that still works like when you were twenty (with a lot of unwanted preconception but also with more wisdom) and since you have a twenty year old ovary (and uterus) you have two more babies. But we would never have enough food to feed that many humans, so we would have to set a law saying no more babies after age fifty. And maybe no more organ repairment after age eighty.

Of course, I say all this because I am not in fear of death at this moment. I respect the wishes of people who are dying or suffering from illness. How could I ever blame humans of their ego in such a situation? It's indeed unfair that some people get to live a healthy life up till hundred while some die before reaching twenty. Genes are unfair. Life is unfair. And tissue engineering has the possibility to grant all dreams of people who wish to live a long fulfilling life just like everyone else.

*In case anyone's wondering, it is apparently possible to treat genetic diseases by tissue engineering. As far as I understand, the very basic idea is that you make iPS cells and replace the abnormal genes (that's causing the disease) with normal ones and then transplant them. You can read more about it in papers like:

Science. 2007 Dec 21;318(5858):1920-3

Treatment of sickle cell anemia mouse model with iPS cells generated from autologous skin.

Hanna J, Wernig M, Markoulaki S, Sun CW, Meissner A, Cassady JP, Beard C, Brambrink T, Wu LC, Townes TM, Jaenisch R.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18063756?ordinalpos=4&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVDocSum

**Nature 505, 641–647 (30 January 2014) doi:10.1038/nature12968

Received 10 March 2013 Accepted 20 December 2013 Published online 29 January 2014

Stimulus-triggered fate conversion of somatic cells into pluripotency

Haruko Obokata, Teruhiko Wakayama, Yoshiki Sasai, Koji Kojima, Martin P. Vacanti, Hitoshi Niwa, Masayuki Yamato & Charles A. Vacanti

http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v505/n7485/full/nature12968.html

(update: this paper is now being considered of retraction by some co-authors for various reasons)

Tissue engineering (or regenerative medicine) seems to be a huge trend these days. In the future, human bodies might be repairable like cars. If your kidney fails, you get a new one made from your own somatic cell. If you need a new liver, you will never have to wait for a doner. If your son is born with a heart disease, you will never have to hope (even for a second) that another child will be brain dead so that he can provide a new heart for your son. One day, you may never have to watch your loved ones die. At least, no nation would have to pay billions of money for dialysis, and therefore, the money can be used to enhance our lives in other ways. It's a technology no one could ever have imagined 100 years ago; it's full of dreams. It's exciting.

And yet, I wonder if we're really heading the right way.

A young Japanese researcher recently published her discovery of a revolutional way of making stems cells from somatic cells by merely exposing them to low-pH (the link is below**). When she first submitted her paper, however, the editor told her that she had mocked the long history of cellular biology. The reason is obvious -- the editor had been soaked in preconception he had formed over many years of editing and researching; he could not believe, or accept that a cell could be reprogrammed with such a simple method.

Steve Jobs said in his famous speech that death was nature's best invention. I agree. Altertion of generations is essential to the progress of human society. The only way the old can give way to the new is to die, or get a new brain with no preconception -- every couple decades, you get a set of new organs along with a new brain for your birthday. Except then, it's not really you. It's just a human with the same set of genes as you. So rather than getting a new brain in a "100 year old" body (with organs of various ages), you might as well be born as a different being with a different set of genes. Then it's called evolution.

Either way, you don't really want a brand new brain. The realistic scenario is probably that you get a set of new neurons that would work along with your old ones so that you can still be you. By the time you reach seventy, you have a brain that still works like when you were twenty (with a lot of unwanted preconception but also with more wisdom) and since you have a twenty year old ovary (and uterus) you have two more babies. But we would never have enough food to feed that many humans, so we would have to set a law saying no more babies after age fifty. And maybe no more organ repairment after age eighty.

Of course, I say all this because I am not in fear of death at this moment. I respect the wishes of people who are dying or suffering from illness. How could I ever blame humans of their ego in such a situation? It's indeed unfair that some people get to live a healthy life up till hundred while some die before reaching twenty. Genes are unfair. Life is unfair. And tissue engineering has the possibility to grant all dreams of people who wish to live a long fulfilling life just like everyone else.

*In case anyone's wondering, it is apparently possible to treat genetic diseases by tissue engineering. As far as I understand, the very basic idea is that you make iPS cells and replace the abnormal genes (that's causing the disease) with normal ones and then transplant them. You can read more about it in papers like:

Science. 2007 Dec 21;318(5858):1920-3

Treatment of sickle cell anemia mouse model with iPS cells generated from autologous skin.

Hanna J, Wernig M, Markoulaki S, Sun CW, Meissner A, Cassady JP, Beard C, Brambrink T, Wu LC, Townes TM, Jaenisch R.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18063756?ordinalpos=4&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_RVDocSum

**Nature 505, 641–647 (30 January 2014) doi:10.1038/nature12968

Received 10 March 2013 Accepted 20 December 2013 Published online 29 January 2014

Stimulus-triggered fate conversion of somatic cells into pluripotency

Haruko Obokata, Teruhiko Wakayama, Yoshiki Sasai, Koji Kojima, Martin P. Vacanti, Hitoshi Niwa, Masayuki Yamato & Charles A. Vacanti

http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v505/n7485/full/nature12968.html

(update: this paper is now being considered of retraction by some co-authors for various reasons)

2013年7月3日水曜日

statistics

Do you think the following foods should be banned?

1. A food that 98% of cancer patients have had daily

2. A food that 96% of rapists ate the day they commited their crime

3. A food that 94% of the people who died of heart stroke had had daily

If your answer is yes, it might be a good idea to study a bit of statistics. The food described in 1~3 is all bread.

In this world full of data and numbers, it's better to be able to interprete what exactly you're looking at.

I'm only writing this to review what I've studied lately, but from what I've learned, the important part is comparison. You can't tell anything from 1~3 unless you compare them with the data of healthy people. If there is no difference, you can't necessarily say the food has anything to do with the conditions above.

The basic hypothesis is "there is no difference between the data of two (or more) groups (2つの集団のデータに差はない)", and the only situation in which you can say there *is* a difference is when you can prove the hypothesis wrong; or in other words, when the probability of the hypothesis being correct is 5% or less (差がある(危険率5%)) which means there *is* a difference with the probability of 95% or higher. If the probablity of the hypothesis being correct is 6%, you can't say there is a difference (差があるとは言えない). But the 5% line is changed depending on what you're looking at; it's just usually set at a low level because you want to be careful when you say there is a difference.

Like when you develop a cancer drug. You probably want to know that the drug really does make a (good) difference before you let your patient go through all the painful side-effects.

Usually, we tend to analyze data assuming that there *is* a difference between two different groups -- like in the example above (normal vs. abnormal), when in fact, there can be many common traits between two groups.

Statistics can probably prevent us from being decieved by our own preconcieved ideas or even hopes.

And apparently, data scientists are said to be the "sexiest professionals of the century". Well, at least in Japan!

1. A food that 98% of cancer patients have had daily

2. A food that 96% of rapists ate the day they commited their crime

3. A food that 94% of the people who died of heart stroke had had daily

If your answer is yes, it might be a good idea to study a bit of statistics. The food described in 1~3 is all bread.

In this world full of data and numbers, it's better to be able to interprete what exactly you're looking at.

I'm only writing this to review what I've studied lately, but from what I've learned, the important part is comparison. You can't tell anything from 1~3 unless you compare them with the data of healthy people. If there is no difference, you can't necessarily say the food has anything to do with the conditions above.

The basic hypothesis is "there is no difference between the data of two (or more) groups (2つの集団のデータに差はない)", and the only situation in which you can say there *is* a difference is when you can prove the hypothesis wrong; or in other words, when the probability of the hypothesis being correct is 5% or less (差がある(危険率5%)) which means there *is* a difference with the probability of 95% or higher. If the probablity of the hypothesis being correct is 6%, you can't say there is a difference (差があるとは言えない). But the 5% line is changed depending on what you're looking at; it's just usually set at a low level because you want to be careful when you say there is a difference.

Like when you develop a cancer drug. You probably want to know that the drug really does make a (good) difference before you let your patient go through all the painful side-effects.

Usually, we tend to analyze data assuming that there *is* a difference between two different groups -- like in the example above (normal vs. abnormal), when in fact, there can be many common traits between two groups.

Statistics can probably prevent us from being decieved by our own preconcieved ideas or even hopes.

And apparently, data scientists are said to be the "sexiest professionals of the century". Well, at least in Japan!

2013年7月1日月曜日

some thoughts

I have a couple of things I want to write about but I don't have much time, so I'm going to see if I can mix them all together and still write an entry that makes sense.

Very recently in Japan, a mother gave the middle lobe of her lung to her three year old son. It was a big news because it's usually the inferior lobe that is used for transplant and it was the first case ever (in the world) that a medical team succeeded in transplanting the middle lobe. The doctor described that when he held the mother's lung to put into the little boy, it felt as though he was "carrying life(命を運んでいる)". He said it was a very touching moment (when he thought about it later).

Around the same time, a famous figure skater disclosed to the media that she had given birth in April. This was a great shock to the public because we all thought she was aiming for the gold medal in Sochi. Now I see that having a baby and winning in the Oympics are compatible (as long as you don't plan to do it at the exact same time). She's still up for the Olympics, and I wish her the best.

But at the same time, I could also understand why some people found the news disappointing. If an athelete wanted to be in best condition she wouldn't choose to give birth less than a year before the Olympics.

Some atheletes say their "goal" in the Olympics is to enjoy. But I don't think the Japanese public are willing to pay to let atheletes merely enjoy themselves. Atheletes should realize that the money invested in them could instead be used to save some sick children with dreams to accomplish -- some might want to compete in the Olympics.

When I told my mother the other day that I thought I might be regareded a bit selfish(自分勝手), she told me that I wasn't selfish but self-assertive(自己主張が強い) and that those were two very different things that were often mixed up in Japan. Having your own opinion and acting according to what you believe can result in selfish behavior sometimes, but you can still be thoughtful of others while being a "strong" assertive human.

Either way, I don't think it's selfish of anybody to choose what they want. People have every right to be assertive when it comes to making decisions about themselves -- it's their life. But maybe, there's something called responsibility too, especially when we're supported by a lot of people.

Very recently in Japan, a mother gave the middle lobe of her lung to her three year old son. It was a big news because it's usually the inferior lobe that is used for transplant and it was the first case ever (in the world) that a medical team succeeded in transplanting the middle lobe. The doctor described that when he held the mother's lung to put into the little boy, it felt as though he was "carrying life(命を運んでいる)". He said it was a very touching moment (when he thought about it later).

Around the same time, a famous figure skater disclosed to the media that she had given birth in April. This was a great shock to the public because we all thought she was aiming for the gold medal in Sochi. Now I see that having a baby and winning in the Oympics are compatible (as long as you don't plan to do it at the exact same time). She's still up for the Olympics, and I wish her the best.

But at the same time, I could also understand why some people found the news disappointing. If an athelete wanted to be in best condition she wouldn't choose to give birth less than a year before the Olympics.

Some atheletes say their "goal" in the Olympics is to enjoy. But I don't think the Japanese public are willing to pay to let atheletes merely enjoy themselves. Atheletes should realize that the money invested in them could instead be used to save some sick children with dreams to accomplish -- some might want to compete in the Olympics.

When I told my mother the other day that I thought I might be regareded a bit selfish(自分勝手), she told me that I wasn't selfish but self-assertive(自己主張が強い) and that those were two very different things that were often mixed up in Japan. Having your own opinion and acting according to what you believe can result in selfish behavior sometimes, but you can still be thoughtful of others while being a "strong" assertive human.

Either way, I don't think it's selfish of anybody to choose what they want. People have every right to be assertive when it comes to making decisions about themselves -- it's their life. But maybe, there's something called responsibility too, especially when we're supported by a lot of people.

2013年6月27日木曜日

what it is to...

It seems like the busier I become, the more things I have that I want to write about. During the last couple of days, my mother told me a couple of interesting things and I wanted to write it down.

1. What it is to be a professional

I've written before that my mother goes to Curves, a female-only gym where she works out every day. She isn't happy with the service she gets there, and has complained (politely) about it to the staffs. But they haven't improved -- they even have a little notice on the wall asking the members to be patient if their service isn't good enough because some staffs are in the process of learning. My mother thinks their problem is that they lack the sense of pride in what they do. "They don't understand what it is to be a professional."

I wonder what patients will say if a new doctor asked them to be patient or toloerant if his service wasn't good enough because he was in the process of learning. It doesn't sound like a good excuse, though I guess patients are called patients because they're supposed to be patient.

It's slightly different but it reminds me of what a famous cram school teacher said to his students. "It doesn't matter whether you like your job or not. You're being paid for it, and when someone pays you, they don't care if you like your job. All that matters is that you take responsibility in what you do. Having pride in your job doesn't mean you like it; it means you take full responsibility and provide the best service."

2. What it is to find a partner

My mother had a shocking moment when she visited me last autumn. After taking a shower, she dried her hair and was tidying up the hair-dryer when I came in and took it away from her. I told her furiously that I hated how she wrapped the twisted electric cord around the dryer. "Make it straight before you wrap it around."

She thought I had become neurotic because of all the anatomy practice. She's glad that I've become a bit relaxed now, but she still remembers the incident when she uses the hair-dryer. The other day, she asked me if I was seeing anyone. When I said I didn't know what to look for in a man, she only said one thing: "I hope you find someone who cares about getting the electric cord straight before he wraps it around the dryer."

3. What it is to die

My mom was doing the laundry when she found a red disgusting bee-like bug. It hadn't gotten into the room yet, but she decided to kill it with a spray because it was "so disgusting". It didn't look like it was going to die so she sprayed a couple of times and watched as the bug eventually suffered to death. "So I realized even bugs suffer when they die. It's obvious, but I felt kind of sorry. The poor thing is still lying on the balcony."

It reminded me of an essay by Naoya Shiga. It was written during his recuperation after surviving a fatal accident. He had realized that death and life were not opposites but that death was part of life. He describes some deaths he witnesses, and one of them is that of a rat with a skewer stuck through its neck. Some children are making fun of it, but the rat tries to live until the end. It doesn't give up; it keeps getting up and trying to get out of the ditch. And Shiga observes that animals are not even allowed to commit suicide.

4. What it is to have a pharmacology test in three days

I have to go back to studying.

1. What it is to be a professional

I've written before that my mother goes to Curves, a female-only gym where she works out every day. She isn't happy with the service she gets there, and has complained (politely) about it to the staffs. But they haven't improved -- they even have a little notice on the wall asking the members to be patient if their service isn't good enough because some staffs are in the process of learning. My mother thinks their problem is that they lack the sense of pride in what they do. "They don't understand what it is to be a professional."

I wonder what patients will say if a new doctor asked them to be patient or toloerant if his service wasn't good enough because he was in the process of learning. It doesn't sound like a good excuse, though I guess patients are called patients because they're supposed to be patient.

It's slightly different but it reminds me of what a famous cram school teacher said to his students. "It doesn't matter whether you like your job or not. You're being paid for it, and when someone pays you, they don't care if you like your job. All that matters is that you take responsibility in what you do. Having pride in your job doesn't mean you like it; it means you take full responsibility and provide the best service."

2. What it is to find a partner

My mother had a shocking moment when she visited me last autumn. After taking a shower, she dried her hair and was tidying up the hair-dryer when I came in and took it away from her. I told her furiously that I hated how she wrapped the twisted electric cord around the dryer. "Make it straight before you wrap it around."

She thought I had become neurotic because of all the anatomy practice. She's glad that I've become a bit relaxed now, but she still remembers the incident when she uses the hair-dryer. The other day, she asked me if I was seeing anyone. When I said I didn't know what to look for in a man, she only said one thing: "I hope you find someone who cares about getting the electric cord straight before he wraps it around the dryer."

3. What it is to die

My mom was doing the laundry when she found a red disgusting bee-like bug. It hadn't gotten into the room yet, but she decided to kill it with a spray because it was "so disgusting". It didn't look like it was going to die so she sprayed a couple of times and watched as the bug eventually suffered to death. "So I realized even bugs suffer when they die. It's obvious, but I felt kind of sorry. The poor thing is still lying on the balcony."

It reminded me of an essay by Naoya Shiga. It was written during his recuperation after surviving a fatal accident. He had realized that death and life were not opposites but that death was part of life. He describes some deaths he witnesses, and one of them is that of a rat with a skewer stuck through its neck. Some children are making fun of it, but the rat tries to live until the end. It doesn't give up; it keeps getting up and trying to get out of the ditch. And Shiga observes that animals are not even allowed to commit suicide.

4. What it is to have a pharmacology test in three days

I have to go back to studying.

2013年6月23日日曜日

inheritance

When Angelina Jolie told the world that she had cut off her breasts to prevent cancer, I didn't really have any opinion about what she did. I didn't think it was *that* tragic to cut off her breasts -- there's more to femininity than breasts could ever speak, and even considering Jolie's profession -- she's not her breasts as much as I'm not my breasts. Obviously.

Neither did I think she was brave and wonderful to have told the public that she had cut off her breasts. The news gave a headsup to women all over the world, but as far as I know, it's not like she has offered to pay for every single surgery needed because of mutant BRCA1/2. She had the money and the support she needed and did what she could to protect herself, just like anyone would do. I didn't really understand what the big deal was.

But today, I was reminded of the difficulties patients and might-be-patients of hereditary diseases face. They want to know the truth, but if they get tested, it might violate the right of their family members -- the right to stay uninformed. It's great if it turns out they're safe, but if not, parents end up blaming themselves and it can also cause some hurtful arguments.

It especially shocked me when an anonymous patient said her mother had told her to give up having a family of her own. She said it was cruel and pointless to produce another human who would have to go through the same pain. It does make sense in a way, but the patient also has the right to live her life the way she wants. Babies are not born to fulfill the parents' desires, but in reality, people have babies because they want babies. If the patient wants a baby, shouldn't she be allowed to have one just like anyone else?

If people start thinking like the mother above, people with hereditary diseases are doomed to suffer discrimination. Our lives will heavily depend upon what kind of genes we have. But we all have genetic deficiencies regardless of whether it shows or not. No one is perfect. And it's hard to define what is "normal".

It seems like science has come a long way. It needs a mature society that can accept what it gives. Maybe this is when ignorance becomes a crime. And I guess Jolie, after all, has given us a good chance to think about something very important.

Note: will be absent till my pharmacology test is over. Take care!

Neither did I think she was brave and wonderful to have told the public that she had cut off her breasts. The news gave a headsup to women all over the world, but as far as I know, it's not like she has offered to pay for every single surgery needed because of mutant BRCA1/2. She had the money and the support she needed and did what she could to protect herself, just like anyone would do. I didn't really understand what the big deal was.

But today, I was reminded of the difficulties patients and might-be-patients of hereditary diseases face. They want to know the truth, but if they get tested, it might violate the right of their family members -- the right to stay uninformed. It's great if it turns out they're safe, but if not, parents end up blaming themselves and it can also cause some hurtful arguments.

It especially shocked me when an anonymous patient said her mother had told her to give up having a family of her own. She said it was cruel and pointless to produce another human who would have to go through the same pain. It does make sense in a way, but the patient also has the right to live her life the way she wants. Babies are not born to fulfill the parents' desires, but in reality, people have babies because they want babies. If the patient wants a baby, shouldn't she be allowed to have one just like anyone else?

If people start thinking like the mother above, people with hereditary diseases are doomed to suffer discrimination. Our lives will heavily depend upon what kind of genes we have. But we all have genetic deficiencies regardless of whether it shows or not. No one is perfect. And it's hard to define what is "normal".

It seems like science has come a long way. It needs a mature society that can accept what it gives. Maybe this is when ignorance becomes a crime. And I guess Jolie, after all, has given us a good chance to think about something very important.

Note: will be absent till my pharmacology test is over. Take care!

2013年6月21日金曜日

creativity

Today we did our last experiment using two groups of mice. We put some inflammation-inducing substance with and without betamethason (an anti-inflammatory drug) on a couple of ears and measured the thickness of each ear every thirty minutes to see the effectiveness of the drug. This time, we couldn't get the results we wanted, but every time I do an experiment, I'm amazed by the creativity of all the past scientists who came up with all the unique methods and instruments.

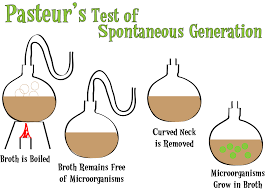

Like Pasteur and the flask he made to trap the micro-organisms in the air. If it hadn't been for his flask, humans still might've believed that living organisms could appear spontaneaously out of no where. Pasteur boiled some broth in his special flask and proved that it didn't rot (=no organisms appeared from that boiled broth) unless some micro-organisms entered the flask.

And even statistics -- we have all these tests that help us prove if there are significant differences between groups. Apparently, we're supposed to hypothesize that there are no difference and do these tests to see if that hypothesis is wrong or not according to the data we have.

Coming from the humanities field, it really impresses me that humans could come up with all these ideas. It sort of reminds me that when I studied the constitution, I was impressed by the idea as much as I'm impressed with the T test now.

Like Pasteur and the flask he made to trap the micro-organisms in the air. If it hadn't been for his flask, humans still might've believed that living organisms could appear spontaneaously out of no where. Pasteur boiled some broth in his special flask and proved that it didn't rot (=no organisms appeared from that boiled broth) unless some micro-organisms entered the flask.

And even statistics -- we have all these tests that help us prove if there are significant differences between groups. Apparently, we're supposed to hypothesize that there are no difference and do these tests to see if that hypothesis is wrong or not according to the data we have.

Coming from the humanities field, it really impresses me that humans could come up with all these ideas. It sort of reminds me that when I studied the constitution, I was impressed by the idea as much as I'm impressed with the T test now.

2013年6月19日水曜日

mouse

I'm extremely tired. I haven't been able to get enough sleep lately, not only because I'm busy with all the experiments and papers but also because I keep waking up at 6:30 for some reason.

Yesterday, we injected morphine to a couple of mice and put them on hot plates and pinched their tails with a clip to see how morphine affected them.

Today, we injected a couple other drugs to some virtual mice on the computer and observed their VBP/HF/HR while another group did the morphine experiment. They worked with the mice right next to us where we were doing our task, and once in a while, when I moved my mouse and tried to move the cursor to a certain place on the screen, it would move on its own -- towards where the mice were.

Either way, vagal reflex is a huge trend lately -- at least around me. Caffeine is supposed to strengthen the heart which means heart rate should rise, but it goes down. Why? It's a result of vagal reflex (caffeine⇒heart↑⇒BP↑⇒vagal reflex⇒heart↓⇒BP↓=back to normal). Norepinephrine is also supposed to strengthen the heart, but heart rate goes down. Why? Again, vagal reflex (α receptors contracts the vessels and BP rises ⇒ vagal reflex ⇒ heart↓) Vagal reflex seems to explain everything. Well, not everything, obviously. It doesn't provide any explanation on why my mouse kept moving towards the mice. Or why I can't sleep.

I feel overall depressed when I don't get enough sleep. Going to bed now.

Yesterday, we injected morphine to a couple of mice and put them on hot plates and pinched their tails with a clip to see how morphine affected them.

Today, we injected a couple other drugs to some virtual mice on the computer and observed their VBP/HF/HR while another group did the morphine experiment. They worked with the mice right next to us where we were doing our task, and once in a while, when I moved my mouse and tried to move the cursor to a certain place on the screen, it would move on its own -- towards where the mice were.

Either way, vagal reflex is a huge trend lately -- at least around me. Caffeine is supposed to strengthen the heart which means heart rate should rise, but it goes down. Why? It's a result of vagal reflex (caffeine⇒heart↑⇒BP↑⇒vagal reflex⇒heart↓⇒BP↓=back to normal). Norepinephrine is also supposed to strengthen the heart, but heart rate goes down. Why? Again, vagal reflex (α receptors contracts the vessels and BP rises ⇒ vagal reflex ⇒ heart↓) Vagal reflex seems to explain everything. Well, not everything, obviously. It doesn't provide any explanation on why my mouse kept moving towards the mice. Or why I can't sleep.

I feel overall depressed when I don't get enough sleep. Going to bed now.

2013年6月8日土曜日

prof and porn

I might be too naive or something but is it only me who finds it uncomfortable talking about sex and porn with a professor? I mean, I don't think it's wrong at all to talk about sex, but at the same time, I think there are more appropriate topics when a student talks with a prof even outside school.